2007

The year of 2014 began in a busy and chaotic, but also amazingly loving, place. Dhaka, the huge and crowded capital of Bangladesh, this small green country almost entirely embraced by India, crisscrossed by rivers and riverbanks and covered in small patches of fields and rice paddies, and inhabited by 160 million people, making it the by far most densely populated country in the world (city-states like Hong-Kong and Singapore aside). It had been a year since we last were here – too long, much too long, and we were happy to be back.

We arrived only days before the parliamentary elections, which were to mark the end of a tumultous year. Bangladeshi politics are much like that, there’s constant rivalry between the country’s two main political parties, and the ongoing tribunal for crimes commited during the war of 1971 had brough all kinds of issues to the table.

So the Dhaka we landed in was a bit different from the city we had left behind. It was in the midst of a series of sudden urban battles where members (well, rather people bribed and picked up around the city) of the main youth political factions fought each others in the street.

Besides that, Bangladesh was very much her familiar and friendly self. Full with generous and hard-working people, constantly finding innovative solutions to life in a cramped, congested city. Life in Dhaka has a pace and energy like nothing else. Street life is more than street life here – it’s like scene after scene from an instant, living, never-ending, never-stopping, urban adventure movie.

B A N G L A D E S H V O T E S

A crowd had gathered in the hall of Dhaka’s main hospital’s burn unit. Doctors and nurses in white robes, people with cameras and microphones pushing their way through. In the midst was a woman and her three children; the youngest of them, a ten-year-old son, was crying, burying his head in his older brother’s chest. Their mum, Halima Akhter, cried out to the people with microphones surrounding her.

“Who will help us? My children all depend on their dad, how are we now going to get by?”

Halima Akhter’s husband, fruit vendor Farid Miah, had just passed away inside the ward, the last of a number of civilian victims of a series of arson attacks against public transportation vehicles in Bangladesh. The bomb, which burned nearly half his body, had been thrown into the bus he was traveling on two weeks earlier.

*

On the day of the elections, all motorised traffic had been banned in Dhaka and businesses and shops kept closed. It was a rare sight in this megacity: the otherwise congested center was still and quiet, its streets empty of busses and cars. The rickshaw drivers were happy – left exclusively with all the customers, without a single motor-driven competitor on the road.

*

Samira Sadeque, who spent the morning at a voting station in Banani in northern Dhaka, saw only seven people vote all morning. She didn’t vote herself either, she says.

“Oftentimes, at least you can vote for the less of two evils. But not this time. The worst thing is the political system here makes you feel that as a citizen you cannot change anything.”

From an update (in Swedish) for Sydsvenskan

2 February

We spent January and February going around the country, following the rivers and its narrow, winding (or dusty, hectic and absolutely straight) roads. We passed by Hindu temples hidden among the greenery and derilict palaces in Old Dhaka; we stopped on the island of Bhola which is literally disappearing bit by bit as a consequence of the changing climate. We got invited to countless cups of tea and plates of rice – and even cooked Lebanese food (loubiyeh bel-zeit, green beans with oil and tomatoes) in a typical outdoors Bangla kitchen (our friends liked it, but they felt it was missing spice!).

We also spent time in Jessore, the last town in Bangladesh before the Indian border, halfway between Dhaka and Calcutta. It’s a typical border town in many ways, with constant movement and people passing through. Everything travels this way: food and medicine, livestock (clue: in one of the countries, cows may absolutely not get killed; in the other, beef is an appreciated kind of meat), clothes and drugs. And people. Trafficking – the kidnappig, forcing, stealing and luring of human beings from one place to another – is a major issue in Bangladesh. Here’s part of a long piece we did for The National in Dubai:

F O R S A L E

”I used to be happy before. Now, I cry a lot in the evenings. I cry because of my fate which brought me here.”

The words belong to Halima, a teenager with a sincere, childlike smile. She stands in a doorway in central Jessore, the last town in Bangladesh before the Indian border. The streets outside are busy, lined with vendors and shops. Everything is for sale here: bananas, rice, hardware, textiles. And women. The doorway leads in to one of Jessore’s biggest brothels.

”I was brought here a few years ago, I lived in the streets at that time. A man took me to Daulatdia, the biggest brothel in Bangladesh. He sold me to the owners, who kept me in a room and gave me drugs. Then, a man suddenly came in and started taking off my clothes. I was so scared, I didn’t understand what was happening.”

Halima continues to tell her story as she walks inside. Clothes hang to dry from the balconies, the air smells of frying oil and chilli. Someone is putting on make-up in front of a mirror. Red lips, a layer of whitening cream covering her face.

Halima doesn’t know her age exactly, but she thinks she’s 17. She has lived in different brothels since that first day when she was taken away.

”I dream about having a family, just like everyone else. But I don’t think I will ever have that life.

Continue reading in The National

3 March

We spent March in one of Bangledesh’s northern neighbours – Nepal, a different place in many ways. No more riverbanks and village mosques, no salwar-kameezes and beards in henna red – instead, towering mountains and urban smog, courtyards and narrow streets, temples in carved wood and stone.

It’s also different because Nepal is a place where people come. Visitors in Bangladesh are rare and few – in Nepal they’re everywhere. In the 60s and 70s, it was the hippies who came to Kathmandu, following the Hippie Trail through Iran, Afghanistan and India; today it’s backpackers and tourists – not interested like their predecessors in cheap and mysterious things to smoke, but in hiking the spectacular mountains. For us, the month in Nepal meant time to work with material we already had: tape recordings, notebook scribbles, photos and ideas from interviews and meetings in Bangladesh.

One story, published as part of a series on the topic of “forbidden love”, came from Cape Cod in northern Massachussets – the very northern tip to be exact, where the city of Provincetown meets the sea. Provincetown is a place like nowhere else, not only on the cape but elsewhere too. Love – rainbow-colored love, free-thinking love, all kinds of love – is truly cherished here.

” W E ‘ R E L I V I N G O N T H E E D G E H E R E “

“Before we start singing, we’re changing some of the words. Each time it says ‘god’, put ‘goddess’ instead.”

We’re inside a wooden church with a high ceiling and red carpets leading up to the altar. It’s mid-morning choir practice, an hour before Sunday mass. The man talking is Jon Arterton, the choir leader and – when it’s not Sunday – free-thinking show artist.

“Then, instead of ‘our father’ we will sing ‘our mother’. We have centuries of male domination behind us, it’s time to make up for that.”

The choir members pick up pens and erasers, replacing the words as instructed. They divide themselves into three groups: alts, tenors, basses. All represent different voices, but the members share one thing in common. They’re in love with someone from the same sex.

We’re in Provincetown, Massachusetts, a small coastal town on the American east coast known also by the name “P-town”. It’s a conventional seaside city in many ways: boats lie waiting in the harbor, restaurants serve fish and seafood, houses have rugged wooden facades. But one thing soon reveals you’re not in a fishing village like any other. The flags. Most houses in Provincetown are adorned with proud, rainbow-colored flags – this is a place where the norm is gay, not straight.

“We’re living on the edge here, in many ways. It’s a place where you’re really free to be who you are. That’s why I can’t live anywhere else,” says Sewall Whittemore, one of the choir singers, as she walks down the stairway after mass is over.

On the way out is a notice board with colorful posters and notes. Meetings with Provincetown’s LBTQ seniors, lessons in “Racial Justice for White People”, an upcoming show with Jon Arterton and his partner. Inside the tiny bathroom, on a table next to a romantic painting of a fisherman, is a box with complimentary condoms. “Love is the spirit of this church”, a notice says.

A short walk from the church (which by the way calls itself a “meeting house”) – past posters for lesbian literary nights and the summer’s Bear Week, and a kitschy garden fountain decorated with Barbie and Kens in army boots and pink glitter – is Napi’s, one of the oldest restaurants in Provincetown. It’s owner, Napi Van Dereck, is also an informal historian of the city.

“Provincetown was always an accepting city, attracting all sorts of people. You know this is where the first pilgrims landed, escaping religious oppression in England?”

He continues.

“Then came the artists, attracted by the isolation and the endless dunes. They just piled into town, they found it easy to live here. Food was cheap, easy to get by. You didn’t need a lot of money to be here, and the population was friendly. This was World War I when thousands of artists and writers and hangers-on poured back into the US. After that, the gays of course. Today, I would say half the people who run the city are gay!”

Part of a story (in Swedish) for Sydsvenskan

“Then, instead of ‘our father’ we will sing ‘our mother’. We have centuries of male domination behind us, it’s time to make up for that.”

4 April

Returning to Bangladesh also meant returning to an absolute, unrelentless heat. The heat in April and May, before the monsoon finally (finally!) arrives, is overwhelming, and leaves you with nowhere to escape. It finds its way inside your consciousness, then stays in your memory and can be evoked in your mind – like a smell or a beloved childhood song.

From now on, the Bangladeshi heat will always bring us back to a particular place – Savar, a sprawling city not far from Dhaka. It was never known outside the country, until April 24, 2013. On that day, only a few hours after the break of dawn, a building in central Savar suddenly collapsed. Thousands of workers were immediately, horribly, buried inside, in the deadliest accident ever in the global garment industry.

We had thought about it a lot in Dhaka. Talked about it, gone to demonstrations and exhibits commemorating the event. On a theoretical level, in our heads, we had an idea of what had happened. That cracks had appeared in the walls the day before, that workers had been sent home. That they had been called back the next morning, told not to worry, to go inside and work – if not, they wouldn’t get paid. That people had entered the building, walked up the stairs to the sixth and seventh and eight floors, where heavy machines and illegal additional structures made the building so heavy that it finally, that very dark morning, just gave away.

We knew that. But it was not before that day in Savar, in that heat (the same heat that had suffocated April 24 the year before), that we came close to actually understanding.

“Then, it all collapsed. Everything went dark and incredibly hot.”

It was not before we sat down with the young football player who had rushed to the site, then home to get saws and heavy tools, then back to try and dig out, drag out, amputate and free, people who were stuck. Not before we met the man who happened to be visiting Savar when he heard the sound of the collapse, ran there, him as well, and began to help, but instead got buried among the others and now, one year later, was in a hospital bed with no ability to move his body and with his little daughter at his side, both with tired eyes and a silent sense of patience. Not before walking around among the rubble that was still there, the pieces of cement and torned strips of clothes, talking to mothers and fathers seeking their children who were still “missing”, only documented on the printed employment contracts the parents held in their hands.

U N D E R T H E R U B B L E

The heat towards the end of April is almost unbearable. Still, crowds have gathered on the site where Rana Plaza used to be, with not a cloud in sight. Family members carry framed photos of their missing sons and daughters; street kids dig through the rubble searching for pieces of iron and things they can sell.

Bangladesh’s garment industry has grown for each year since it was established in the 1980s, and today it makes for ¾ of the country’s total exports. After China, Bangladesh produces more clothes than any other place in the world. Sweden, like most other countries in the West, is a top consumer. In 2012 and 2013, we imported clothes with the tag “Made in Bangladesh” for 4,5 billion SEK.

The Rana Plaza collapse was not a singular event but one among many. Fires, workplace accidents – no one knows exactly how many people have died in all, but incidents are reported (or not reported) each year in the country’s 5 600 factories.

Only a short rickshaw ride away from the site is CRP, a big hospital and the only physiotherapy clinic in Bangladesh. This is where many victims were rushed after the collapse – and this is where many still remain.

At the far end of the hospital area, nearby the workshop making artificial arms and legs, sit rows of simple brick buildings. Families stay here to get accustomed to life with their new body parts, or crutches and wheelchairs, before moving back to their homes again. 24-year-old Rihanna, who only uses her first name, used to work on the seventh floor of Rana Plaza. She walks with careful steps, one step at the time, ducking for colorful scarves and tunics hanging to dry. Her right leg is the same she always had; the left one is made here at CRP, replacing the one she lost in the collapse.

“They had sent us home the day before because they noticed cracks in the building. But then in morning they said everything was fine, that it was safe to go in. That we wouldn’t get paid otherwise. So we went in. Then, it all collapsed. Everything went dark and incredibly hot. A wall fell down on my leg and crushed it.”

Back at the site, evening is about to fall. The crowds are still there, the heat remains intense. The walls are covered with posters, large ones, printed for this occasion. A large banner, fastened with ropes, says: “Rana Plaza. Never again”.

From stories (in Swedish) for Hufvudstadsbladet and Sydsvenskan

5 May

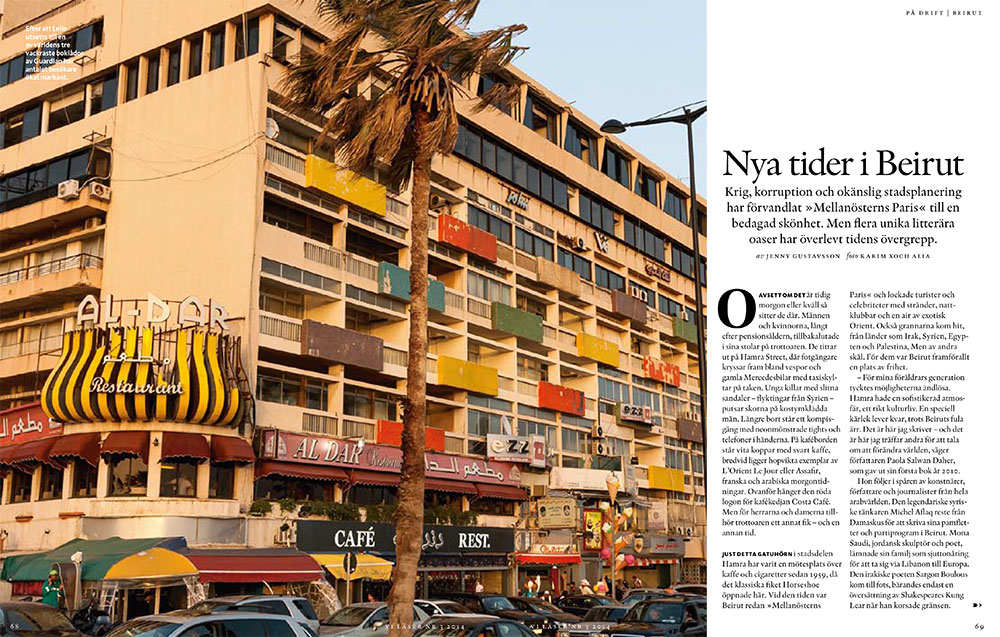

Another piece we worked on in Kathmandu, to the sounds of early morning puja and speeding motorbikes, and only leaving the computer to get hot momos stuffed with vegetables and soft paneer, was a story from home. From Beirut. Vi läser, a magazine about books and literature published in Sweden, has two spreads in each issue inviting readers to a place somewhere in the world. We had earlier done a story from the childhood home of Bengali giant Rabindranath Tagore; this time we wrote about Hamra, an iconic part of cultural Beirut.

A C U P O N H A M R A S T R E E T

No matter when you pass by – early morning, midday or after dark – they will be there, seated comfortable in their chairs. The men and women, all past their retirement age, with ashtrays and small cups of coffee in front of them, gazing out on the street – Hamra Street, with its smooth and organic chaos of old Mercedes taxis, delivery guys on vespas and people crossing the street. A bit further down on the pavement, young kids with worn clothes are shining shoes. A group of friends walk past them, with neon tights and smartphones in their hands. Next to the ashtrays on the tables are folded issues of the morning newspapers: L’Orient-Le Jour in French, and Assafir in Arabic.

*

By the early 1970s, Hamra Street had a number of (already iconic) coffee shops: Horseshoe was there since ten years back, frequented by the likes of Adonis, Syrian journalist Ghada al-Samman and a visiting Samuel Beckett; next door was Café de Paris, with brightly colored outdoors tables and chairs; opposite on the other side was Modca and, of course, Wimpy, where Yasser Arafat and his comrades came to meet.

“In the sixties and seventies there was one ‘coffee’ – that’s what we called them – for each group. The communists, the poets, the Naserists; all had their own place and atmosphere,” says Khaled Bedeir, more known in Hamra under the name Mike. Since 1952, he’s cut the hair of customers in his small but legendary Mike’s Barber Shop.

“They all came to me – ambassadors, politicians, journalists. Once, even [murdered Swedish prime minister] Olof Palme was here.”

But everything was soon about to change, for both Mike and the coffee shops. For all of Lebanon. In April 1975, 27 people were killed on a bus in one of Beirut’s suburbs: that marked the first incident of what was going to be a large-scale conflict, involving neighboring countries (both of them) and global powers, and not reaching an end until 1991. The climate in Beirut changed quickly: tourists were asked to leave, people’s daily lives began to smell of fear and despair. Playwright scripts and revolutionary pamphlets were cleared from the café tables, instead, customers sat down to hear about the latest fighting.

*

Today, decades after the end of the war, Hamra Street is again lined with shops and cafés. The streets never really sleep, neither do the people – the shopkeepers, taxi drivers, trash collectors, students and the kids in the street. The area remains a place for gathering writers, only now the Horseshoes and Wimpys bear names like Mezyan or T-marbouta, and notebooks are replaced by laptops with glowing symbols of a fruit.

There’s this idea that you can get a sense of Beirut by visiting her coffee shops. That the talks across their tables say something about the city and its inhabitants. In that case, Hamra remains her usual self: always there, only in constant change.

From a piece (in Swedish) for Vi Läser

Artists, writers and journalists from all across the Middle East found in Beirut what they missed at home. Michel Aflaq, the legendary Syrian thinker, came from Damascus to write his pamphlets in Beirut; Mona Saudi, sculptor and artist from Jordan, travelled through the city as a 17-year-old, en route from her parents' house to Europe. The Iraqi poet Sargon Boulous crossed the border to Lebanon by foot, carrying nothing but a translated copy of Shakespear's King Lear.

6-7 June-July

Last year, Swedish crafts magazine Hemslöjd got awarded not once but twice – first as #1 cultural publication of the year, then as the recepient of the Swedish publishing award. Much deserved: the team behind Hemslöjd put a lot of work into making it smart and thoughtful. Here are two features we did for them during summer:

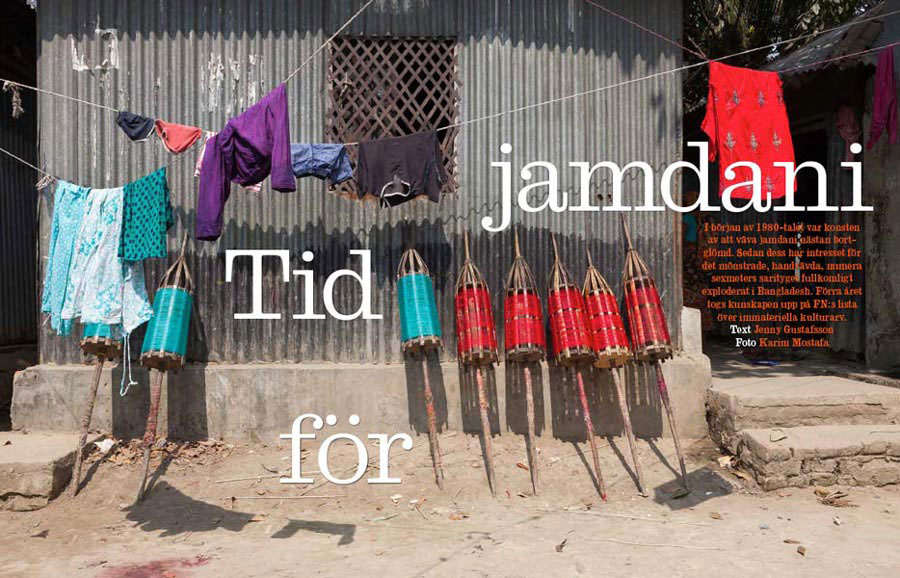

First the story of jamdani, a delicate Bengali weaving craft dating back to before the Mogul times. Only a few decades ago the art was close to disappearing – then, a woman from Dhaka named Monira Emdad discovered the few remaining artisans and started what was to become a revival, which has enabled the community of small-scale artisans to grow and preserve their craft.

T I M E F O R J A M D A N I

At first glance, South Rupshi looks like any other village in the Bangladeshi countryside. Tea stalls line the roads, kids play in the mid-day heat, rickshaw-drivers pedal their decorated bikes. But this place is different. Bundles of yarn in bright colours hang to dry in the sun. People sit on their porches, spinning threads onto spindles. Inside almost every home, a traditional loom is set up. South Rupshi is a village of weavers – the ancestral home of a proud, age-old craft.

The main road in the village is lined with small tin houses. Inside one of them, side by side behind a wooden loom, sit Parbin and Abdul Salam. They’re a married couple – but also lifetime colleagues.

“We spend each day here, morning to evening, weaving together. It’s a good job now that jamdani has become more sought-after. It’s clean and safe, which many other jobs are not. And we can work together at home,” says Abdul Salam.

*

These days, South Rupshi’s weavers are busy. There’s a high demand for saris, and enough work for people to support their families. But this was not always the case. Only a few decades ago, traditional weaving was a forgotten heritage. Until sari entrepreneur Monira Emdad brought it back to memory.

“In the early 1980s, when I was traveling in rural Bangladesh, I came across these hand-woven saris, more beautiful than I had seen anywhere else. Back then, they were only worn in the villages. It was impossible to find fabric of that quality in the cities,” she says.

She immediately sensed the potential of the hand-woven textiles, and started bringing saris from the villages to Dhaka, where she introduced them to her friends.

“Soon, I operated a small sari shop out of a tin shed in central Dhaka. I brought new designs and colour combinations to the weavers, based on what the urban customers wanted.”

*

With the growing popularity for jamdani, opportunities for the producers are changing. Last year, UNESCO declared jamdani an intangible cultural heritage, stating its importance as “a symbol of identity, dignity and self-recognition”.

“We have many customers now, which is good. Shopping malls and outlets pay well. But our families, those who make the saris, still cannot afford to wear them. Salaries for common people here are much too low,” says Muhammad Jahangir.

The weavers earn about 200 to 500 taka per day ($2.5-7), little more than someone working in Bangladesh’s garment industry, where the monthly minimum wage is 5300 taka ($70).

“But this is much better for us. We can stay in the village and work nearby our families. And it’s not dangerous, we only use our brains here,” says weaver Mohammad Azim.

From Hemslöjd’s issue about The needle

The next story came from Guatemala, where members of the Mayan population wear handmade and beautifully decorated blouses called huipils. To the community, the huipil represents a continuation between the past and present; to others in the streets of Guatemala, it functions as a reminder of the country’s unique Mayan heritage. Ixquik, a woman we met in the mountan town of Zunil, said that to her, the huipil is like a book, chronicling the living past and present history of her people.

C R A F T E D S I S T E R H O O D

“The historical Mayans were strong and intelligent, but they didn’t write any books. They passed on their traditions like this, through their hands.”

Alejandra Micaela Ujpán, from the small town of San Juan La Laguna in central Guatemala, holds up a heavy blouse with decorations in deep, shifting colors. It’s a huipil, the traditional dress still worn by many from the Mayan community.

“To me the huipil is sacred. It connects me to our ancestors, links me to the past. I always wear the huipil, every day. From different parts of the country, not only from here. It’s the product of the hard work of a fellow Mayan woman,” she says.

“The blue color represents the lake, the green the mountains. The decoration around the neck is a rainbow, or xokon-a, in [the Mayan language] tzutujil.”

Just below the collard, on the front of the blouse, is an embroidered geometrical pattern. It represents the nahuals of the Mayan tradition, says Alejandra Micaela Ujpán; 24 protective totems, derived from the animal kingdom.

Nowhere else in Central America has the Mayan culture managed to survive and reinvent itself like in Guatemala. A major part of the population identifies as Maya (official statistics say 40 per cent, but many believe the real number to be close to 60 per cent), and the traditional textiles are strong markers of this trans-regional culture. The huipils – and the people who wear them – have survived attempt after attempt at marginalisation and destruction: centuries of repression and discrimination, culminating most recently in the horrendous 1960-1996 Guatemalan civil war, when 200 000 people were killed, mainly civilians from the Mayan population.

“At that time, wearing the huipil was dangerous. The clothes became a way of identifying people, because they tell where you come from and where you belong. My husband was a victim during the war, he was taken away and tortured by the military. He still has the marks on his arms and neck,” says Alejandra Micaela Ujpán.

From Hemslöjd’s issue about Linen

[/aesop_content]8 August

Part of a photojournalism workshop Karim did in Antigua, the old colonial capital of Guatemala, was documenting a segment of life in or around the city. Antigua is a very touristy place, with cobblestone streets and houses in dusty pastels, but with outskirts and a dusty market home to workers arriving from the mountains, children with shoe-shining boxes, and those with nowhere to sleep.

It was through some of these Antiguans that Karim got in touch with La Luz de Jesus, a place hidden in the greenery outside of neighboring San Lucas. People come there get rid of their addictions – all kinds of people, fathers and grandfathers with regular jobs, abandoned teenagers, and those who literally have been picked up from the street – lying in a pool of water or outside a cheap and shady bar.

“He was lying in a pool of water. What’s sure is that if he would’ve stayed in the streets like that he would be dead by today. He was so cold we thought he had died.”

We worked on another story in August too, one of the very big and important Central American issues right now: how millions of men and women, often very young, leave Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador and try, with all means possible, to reach across the U.S. border. Thing is, many of them come back. They’re deported, put on chartered planes, flewn across the country and back to where their journey started. Back to square one. We spent time at the airports in Guatemala City and San Pedro Sula, where several flights with deported migrants land every day.

N O P L A C E L I K E H O M E

A small crowd has gathered on the grass outside Guatemala City’s airport. They wait patiently, milling about outside the gates. Suddenly, a plane appears in the sky and sinks behind the wall. It’s the sign that everyone has been waiting for – one of flights filled with men, women and families deported from the United States that land daily.

“I’m here to meet my brother. He called us yesterday saying that he was coming back today,” says Azucely, a young woman with one child resting on her hip and another playing at her feet.

Her brother had been in the US for five years, she says, when he got caught without papers. The police held him in custody for months before deporting him – at first, he didn’t want to sign the deportation order. Azucely herself went through the same ordeal only a year before.

“I had been in the US for nine years when I was deported, all the time without papers,” she says. “I have three kids born over there. I left Guatemala when I was young, only 14. My mum took a bank loan to send me. She did the same with my brothers too.”

Azucely and her family are far from unique. Their experiences are part of a common narrative among young people from the region, who are migrating in ever-growing numbers. The Central American immigrant population in the US has nearly tripled since the 1990s, and now makes up the fastest-growing segment of the US Latino population. But many stories have a very sudden end – with deportation and a one-way ticket to whatever country issued their passport.

“Each week, between nine and 14 flights land here, full with people. Most come with nothing at all. We give them juice, bread and beans. They can call someone in their family,” says Mario Hernández from Asociación de Apoyo Integral al Migrante, a local migrant support group.

He stands under a modest shelter right inside the airport walls. A big sign says: “Welcome to Guatemala. You are with your people in your country”. There’s a phone on one of the tables and a poster from a shelter home in the city where people can sleep if they have nowhere to go.

Outside the airport, more people have gathered to wait. Eventually the heavy gates open with a click and families move closer in expectation. A young man in uniform lets the people waiting on the other side out, one by one. When Azucely’s brother finally appears in the trickle of deportees, their mother starts to cry. She hasn’t seen him in five years. As the family walks away, Azucely says that they are going home to their village in Guatemala’s south-west.

“I don’t think we will try to go back another time. There are so many police in Mexico now, and it’s dangerous crossing the border. Also, mum says no. It’s too expensive – and we’ll only get sent back again.”

From a piece (in Norwegian) for Aftenposten Innsikt and (in English) for The National

“I worked as a mechanic at the airport. In Tampa, Florida. Very hot. I came across the border, through Mexico. No visa, no work permit, no nothing like that. Guatemala has become expensive, but wages are minimal. The restaurant, Pollo Compero – you have to work for one day to pay for a meal there. In the US, if you work one hour you can buy two hamburgers.”

9 September

From Guatemala we continued south, crossing the border to nearby Honduras. Another world in many ways – more laid-back and green, with a tropical heat and soft beaches, heavy papayas and simple wooden huts overlooking the ocean. And the beans are red, not pitch black like in Guatemala.

The first place you reach after the border, an hour or so on a bus along the coast, with endless banana plantations and newly erected palm oil farms lining the road, is San Pedro Sula. We spent a couple of weeks in the city, known for its easygoing and friendly attitude, its businesses and industries – and, for being the most dangerous city in the world. More people than anywhere else get killed here each year, and violence has grown to become an ever-present part of daily life. Inevitably, it’s shaping people’s lives.

N O W H E R E M O R E D A N G E R O U S

San Pedro Sula, close to the border with Guatemala, is the industrial capital of Honduras. Known for its tropical climate, its friendly attitude – and its murders. The city is number one in global homicide statistics, with 187 killings per 100 000 inhabitants each year. Number two, Venezuela’s Caracas, and three, Mexico’s Acapulco, are far behind, with 134 and 113 murders per 100 000 people respectively.

For the people in San Pedro Sula, death has inevitably come closer. It’s like what Frantz Fanon, the post-colonial thinker, said: violence, once it has been introduced into society, can never leave. It grows roots, enters people’s minds. Becomes part of what is normal.

A young man who calls himself ‘La Fresa’ tells his story. He talks about his family – wife and a little son – and childhood – with different foster families, all very poor. But he reveals no details about places, no names. He lives his life in hiding, secrecy. Since he was a young teenager, he has made his living as a sicario, a hit man.

“I have several guns, fifteen all in all. But this is my favorite. It’s killed 32 people.”

La Fresa puts a polished gun on the table in front of him. He wears sneakers and a football t-shirt, pulls a balaclava over his face for the portrait photo, but removes it as he starts to talk. He’s part of an “organisation” he says, assassinating people for money. Mostly rich and elite figures – business men and politicians, people with powerful enemies.

“But I feel no guilt. What happens to them is their destiny. If I felt guilty I couldn’t do this. The only time I feel something special is when we kill mareros, gang members. They’re brutal and murder families and kids, so taking them out feels like the right thing to do.”

Still, he’s about to do his last assignments soon, La Fresa says. He doesn’t want to continue any more – he just lost his best friend and partner in the organisation. And his kid is growing up.

“There’s this song that goes ‘When I was little I wanted to be where I am now.’ That’s how I feel. When I was young I had nothing, today I’ve come somewhere. I wanted to be a judge or a lawyer, but instead this is where I ended up.”

Part of stories (in Swedish and Norwegian) for ETC and Aftenposten Innsikt

San Pedro Sula is also like any Central American city. Its city center is busy, with street markets and cramped streets leading out from the central Parque. People sit in the shade under big trees, vendors carry boxes with cigarettes and cheap chewing gum around their necks. Towards the western edge of the city, a the foot of the green Merendón mountains, the sprawling suburbs take over. The streets here are lined with colorful fast food chains and houses behind high walls.

“We're the only ones left, the neighbors have fled. The constant insecurity, the gangs. My mum left, she has diabetes and the shootings affected her pressure. But she returned recently, and a few neighors are starting to come back. The police says it's 'mara free' now, but we don't know.”

“I have fifteen all of all, but this is my favorite gun. It's killed thirty-two people.”

For the people of San Pedro Sula, death has come closer. It’s like what Frantz Fanon, the post-colonial thinker, said: violence, once it has been introduced into society, can never leave. It grows roots, enters people's minds. Becomes part of what is normal.

10 October

October is a good month in Bangladesh, the rains have stopped and it’s getting a bit less hot. This means business for one of the biggest sectors in the country: the brick-making industry. Autumn and winter is the high season for brick production, and the 10 000+ fields across the country, covered in a layer of orange dust and employing millions, are simmering with activity.

“My name is Hashi, which means smile. It's like me. I always smile to people.”

1 0 0 0 0 C H I M N E Y S

Bangladesh, with 160 million inhabitants, is a country urbanising incredibly fast. The need for cheap and available building material is constant, and serves as the driver for one its biggest industries: brick-making. Millions of bricks are burned each year, on simple fields across all of Bangladesh.

“It’s very easy to get started with brickmaking,” says Shamim Iftekhar of the UNDP in Dhaka. “All you need is a small piece of land and 40-50 lakh taka [$6000]. In half a year, you can get five times that investment back.”

Almost all bricks produced today are made using a technology from 150 years back, and has changed little since. Soil is mixed with water, formed into bricks using wooden forms, then left to dry in the sun and burned in traditional kilns.

Nearly every part of the process is done entirely by hand, by workers of all ages; grandmothers work next to children, shaping the bricks with rapid movements; young men and women carry stacks on their heads, from field to kiln, kiln to truck. Many come from rural parts of Bangladesh and stay for months at a time at the fields. Payment is irregular, the work monotonous and heavy.

“This is an industry with absolutely no regulations. It’s a place where people get hurt or die but nothing happens,” says Saydia Gulrukh, an activist for workers rights.

The city of Khulna, like most Bangladeshi cities, has brick fields scattered in the countryside all around. A large field stretches along the banks of a river, right south outisde the city. The sun has reached its peak and there is nowhere to seek relief and shade. A group of men, all with lunghis tied casually around their hips, dig mud from a hole in the ground. Their arms are thin but strong, covered in layers of dry and cracked mud. A stream of women, men and kids walk past them, with rubber sandals or no shoes at all, and scarves tied around their heads, carrying stacks of bricks on top. Back and forth, back and forth, until the workday is over.

Robia, ten years old, unloads her bricks, then unties her scarf. Someone takes out a mobile phone, starts playing a Bengali song – a hit, because people know it. Robia smiles and starts dancing, kicking up dust around her feet.

“No,” she says, “I don’t want to work here when I grow up. I want to become a dancer.”

Featured on Al Jazeera and (in Swedish) in Dagens Arbete

11 November

After almost a year spent between Bangladesh and Central America, we returned to Beirut in November. One step outside the airport and you’re back: the smell of fumes and narguilehs stuffed with apple tobacco; the fearlessness and charming/mad traffic maneouvers; the eternal waves rolling towards the Mediterranean shores.

Many Novembers have passed since we first came to Beirut in 2009 and 2010, but for one reason or another, we have never been in town for a special and, since 2003, reoccuring event: Beirut’s very own 42k race. Until this year.

New York, Berlin or Marathon’s Marathon – whatever kind of marathons they are, the one in Beirut is different. The Lebanese capital is known (and rightly so) for its many paths that lead in different directions, and for the diversity (and at times divisiveness) of those who thread them. But on rare occasions, all paths seem to lead the same direction, allowing people to walk together and not apart. Beirut Marathon (well, technically you should run, not walk) is one of them.

R U N B E I R U T , R U N !

Since months back I had been following the lead-up to Beirut Marathon, a race that’s been organised since 2003, only growing bigger for every year. It has survived – outsmarted, perhaps – the usual outbreaks of political conflicts; not even in 2006, after the destructive July war, was there talk of cancelling (instead, the race that year was called “For love of Lebanon”).

On the morning of the race, it was as if all clouds for a moment had disappeared from the Lebanese sky. It was sunny, and it seemed that everyone had took to the streets – literary, ready with their running shoes and numbers across their chests.

The race is a marathon, but the marathon runners in reality are only a small minority – maybe 500 or so of the total 37 000 who had signed up. Many are not even there to run, only to take part. Families with strollers, groups of friends, those who walk from start to finish.

Or workplace colleagues from all parts of the country, like the runners from UNIFIL, the international peace-keeping force in the south, all in UN-blue t-shirts and accents from India, Korea or Bangladesh. Others wore t-shirts said things like, “I run for cancer,” or the official race slogan, “Peace, love, run”. Runners in bridal gowns protested against child marriage; a team of diplomats from different embassies symbolically passed the stick from hand to hand.

From a column (in Swedish) for Sydsvenskan

12 December

Finally, December. Always decisive, marking the end of an era and the beginning of another. We were still in Beirut, watching the evenings grow darker and days windier, spending time to work on both new and old things. We visited many Syrian families living in garages, half-deserted buildings and make-shift tents. It’s been nearly four years since the refugees started to arrive in Lebanon, and two years since they came in large numbers, but the situation remains the same. It’s only the kids that have grown bigger, the memories older, the distance farther. And Lebanon, tiny Lebanon, is all of a sudden home to more refugees per capita than any other country in the world.

Also, before leaving 2014 behind, Karim digged deep into his photo archives, stopping at November 2011 and Cairo’s “battle over Mohammed Mahmoud” – one of the big protests of that revolutionary year – which he shared in a feature for Australian Flint Magazine.

B A C K T O T A H R I R

What began as a peaceful protest turned increasingly violent, as riot police were employed in the neighbourhoods surrounding Tahrir. Mohammed Mahmoud Street, leading up from the square alongside the American University of Cairo, became a literal war zone, at once filled with panic and ad-hoc organised protestors.

It quickly acquired significance among those fighting for their city, and the walls lining the street filled up with beautiful works of art. The young people who lost their lives were portrayed as angels, and graffiti promised they would never be forgotten. Many were painted with patches over their eyes, symbolising the injuries people had from getting shot by riot police, or from the strong tear gas used against the protestors.

Today, more than three years later, Egypt’s Tahrir generation continues their battle for a peaceful, free, civilian state. Some of the most prolific activists are in prison, as are many members of the Muslim Brotherhood, the Egyptian army’s foremost contester to power. The graffiti on Mohammed Mahmoud has been removed and painted over several times, but the angels and their memory remain.

More in Flint Magazine

Next chapter: 2015!

Photos by Karim Mostafa, text by Jenny Gustafsson